Eyes to See: Approaching the spiritual in world art

Reproduced with permission from Foreword Magazine, Reviews of Indie Books since 1998, to mark the publication of Eyes to See on February 3, 2026. The interview was conducted by Jeff Fleischer.

- Having written many previous books about art, how did you decide to write Eyes to See and to focus on artwork with a spiritual component?

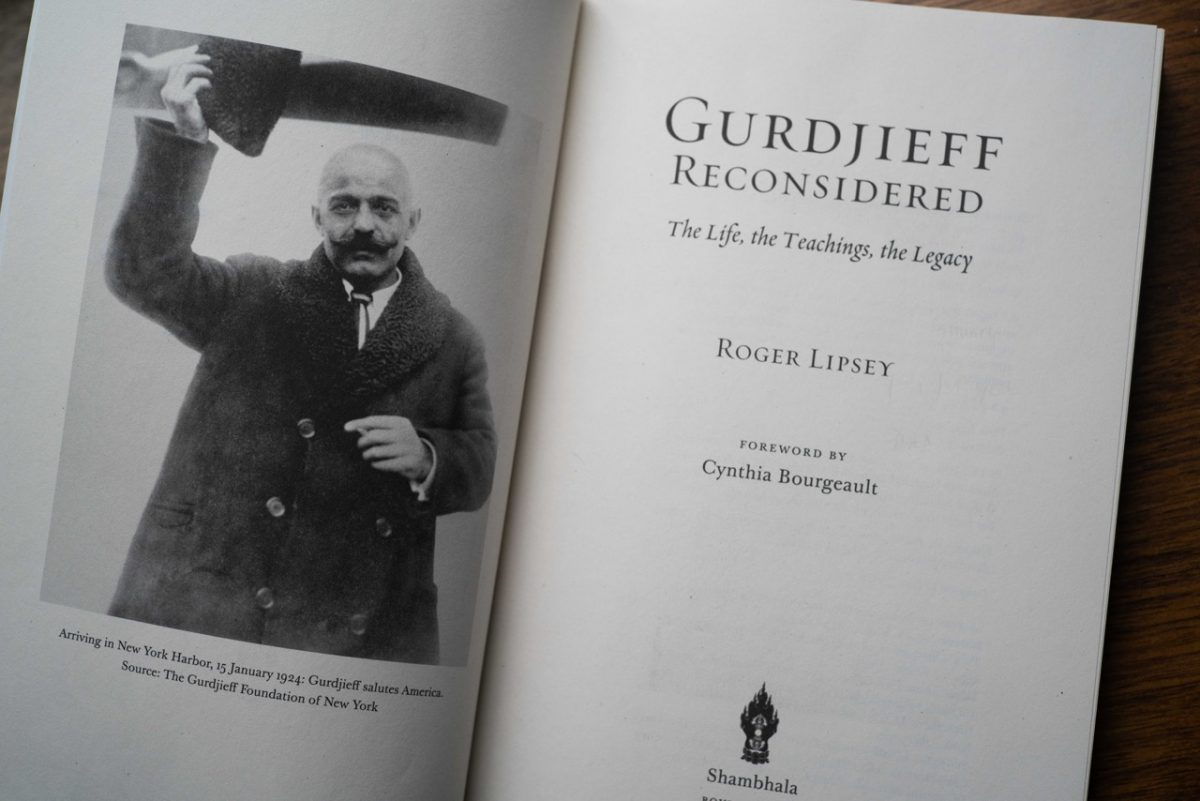

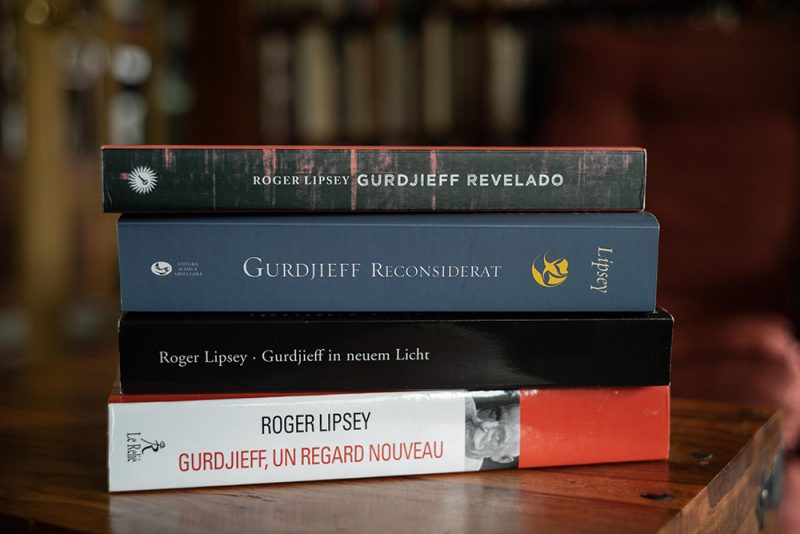

I remember writing these words toward the beginning of Eyes to See: “I didn’t need art that reflects my day-to-day self—that was evident enough. No, I needed to know what I am, what we all are essentially. I needed to see that. I was patrolling the universe of images for clues to my identity and the identity we all share.” In my experience, a sound approach to the spiritual in art begins with a question and quest of this kind. Then you begin to find and dwell for a time with works of art that speak to you, they are messages from everywhere. They remind us of what we are—of our potential, of our obligation as human beings. Works of art carrying and communicating these messages from everywhere help us to think, feel, and be. They widen our horizons, deepen our love of life. Since I began study of art history, I’ve never had another focus. I owe it entirely to two outstanding teachers: Ananda K. Coomaraswamy and G. I. Gurdjieff.

- The book covers a wide range of art from around the world and from different periods of history. With such a range, how did you begin narrowing which works you would include?

Both Coomaraswamy and Gurdjieff were profoundly cosmopolitan in their scope and interests, literally citizens of the world. Thanks to their inspiration and example, I have explored many cultures, many worlds of art and craft. And I should note here that I don’t make a sharp distinction between art and craft—between, let’s say, sculpture and ceramics. Where all the distinction lies is in the quality of the makers’ attention, in the skill of their hands, in their purpose. There is a tradition in Hindu and Buddhist art that the sculpted figure of a god or goddess comes to life only when the eyes are painted in: the last gesture in an age-old process. By analogy, something like that is true of all genuinely fine art and craft. The painting, the carving, the intricate weaving, the glazed bowl is endowed with life and spirit by the excellence of the artist, the intrinsic beauty and truth of his or her theme and purpose. Spirit finds its way into things and stays. For Eyes to See, I chose works of art and craft at this level of excellence.

- What new realizations did you have about specific works of art as you thought about them in terms of Eyes to See? Any pieces you came to see differently than you did before starting the book?

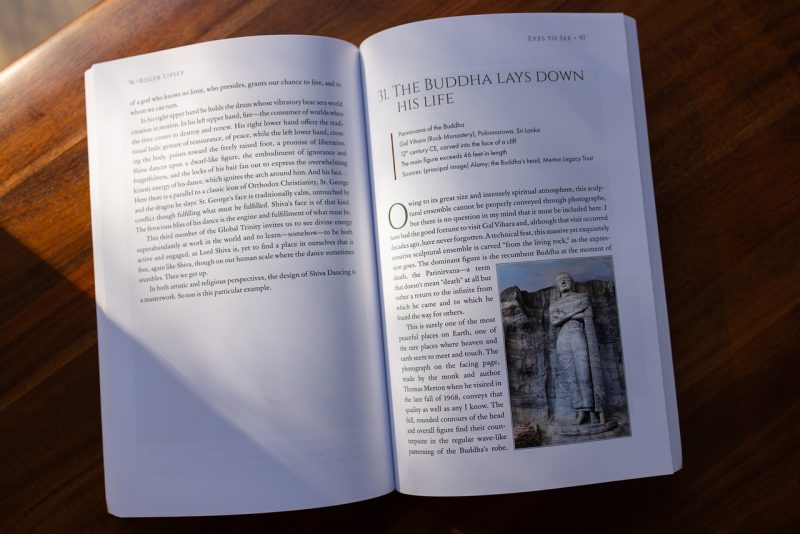

For it to be an honest book, I had to revisit the history of every work and its aesthetic and spiritual nature. It’s no exaggeration to write here that I knew it was my business to perceive anew every one of these works of art. What became a joy for me as I composed the book was to offer to you—my friends known and unknown—a vision of art that can, if you wish, become integral to your lives. I hope that you will become, in turn, an icon collector, that you will understand that art and craft of all times and places is a mirror, returning us to ourselves with new insight. Consider the awesome dignity of the Khafre-Horus sculpture and its conception of our relations with the divine; allow Rembrandt’s people to teach us to see, yes, mindfully; allow Muslim calligraphers to show us how to respect the Word—and so much more. All bright mirrors of the scope and depth of what is possible when we care, when we work ever so hard, when we aspire and derive our happiness from caring, working, aspiring—and achieving.

- In terms of mediums, the book covers everything from sculpture to tomb art to illuminated manuscripts How did you decide which mediums to include? Where did you draw your line on what falls outside the scope of the project?

I never had the impression of drawing a line. I knew what I wished to include—for example, woodblock prints by Hokusai and Hiroshige—and so the fascinating question became which prints to include. I knew that I wanted you to see one of Hokusai’s transcendently beautiful and moving images of Mount Fuji—but which one? I knew that the wonderfully complex prints and psycho-cosmic vision of Robert Fludd should be included, and there were many possibilities. And so it went. I also knew that there are phases of art—times, places, cultures—that I couldn’t touch or include, for example the very beautiful Aboriginal art of Australia, both the ancient petroglyphs and the new transcriptions to canvas of traditional songlines. For decades I have admired this art from afar but could not present it to you with reasonable authority.

- After completing the manuscript, what surprised you most about the journey through these artworks?

I suppose this book was incipient, waiting to be written, for many years. What surprised me, and continues to surprise me, is that I was somehow able to be completely honest, to share the vision of art, and the search through art, I have had for so very long. That vision, however large or small, is the product of learning and love, of intense academic study and of engagement with spiritual practice and values. Could such a thing be spoken, shared? This book is the answer: yes.

- What do you most hope the audience comes away with after reading Eyes to See?

I hope that its readers will, in turn, become icon collectors. It’s not about collecting actual works of art, though you would be surprised how many wonderful images and objects can be found in “flea markets.” The icon collector is looking for signs of himself, herself in the art of the world—not our ordinary, day-to-day selves, but something else: our real aspiration, our real sensitivity, our real sense of things. Our real identities, the fundamental human, hidden but discoverable. We can know ourselves at that depth I suppose only in flashes, only sometimes. That matters, it adds lines to our inner compass, and with eyes to see, we will see. Approaching the spiritual in world art is to approach the spiritual in ourselves.