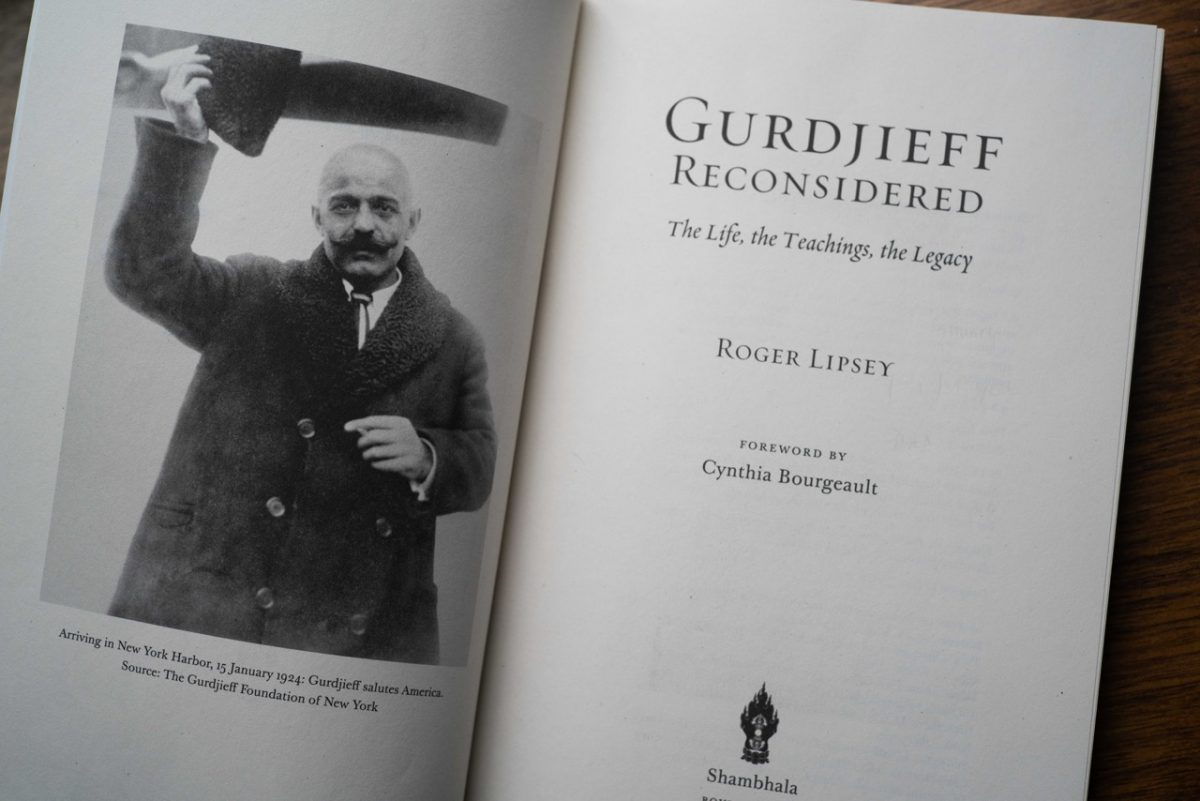

Gurdjieff Reconsidered: The Life, the Teachings, the Legacy

With a Foreword by Cynthia Bourgeault

Shambhala Publications (2019)

This entry is excerpted with permission from the May 2019 issue of Mind Body Spirit, published by Watkins Books, London (www.watkinsmagazine.com)

When I set out to write, I perceived no need for “another Gurdjieff book,” another exposition of the teaching that could not help but echo, loudly, the large and in part marvelous literature already in print. But for years I have had something else in mind, awaiting its time.

Gurdjieff taught quite differently from decade to decade in the West, and in some respects, he was a different person. He too evolved, worked on himself, responded to the constraints and opportunities of changing circumstances. Gurdjieff Reconsidered listens to him, and up to a point biographically chronicles him, in four successive periods: the first teaching cycle (Russia, 1912 – 1917); the Institute he founded at Fontainebleau-Avon (1922 – 1932); Paris in the 1930s when he was living modestly with few but gifted pupils; and finally the Occupation and post-war period in Paris when he taught at his apartment, rue des Colonels Renard, and in rehearsal spaces at the Salle Pleyel for the sacred dances or Movements.

“Once in Russia,” Gurdjieff recalled, “I lived like a gypsy. I had a horse, donkey, tent, friends. I make 20 or 30 kilometers one day, then stop rest two days. Only such travel is real. Then you know how is—you know if each place has two or three stones. Go this way from Paris to Turkestan and will complete education have.” I wrote in this spirit. His decades set successive boundaries; I wanted to see and share those two or three stones—and many more—that made each period distinctive and deeply interesting. If there was to be teaching in this book, it would be delivered by Gurdjieff himself and those closest to him; hence what must be hundreds of anecdotes and records of unique conversations gathered from published literature and previously unexplored archives. They are flashes of insight, flashes of light. One early reader of the book called it a “reboot”, a renewal of our vision of Gurdjieff. I hope that you will find it so.

In my concern to see Gurdjieff whole, the book explores not only his work with pupils but also his choreography, the music composed in collaboration with Thomas de Hartmann, much of it dating to the mid and later 1920s, and also some of the more difficult writings. Gurdjieff cannot be understood without knowing at least a little of these aspects of his sustained creativity. I wanted to see him whole and to share that vision.

In his lifetime (1866 – 1949) and in decades after, Gurdjieff was by and large expelled from Western culture, from serious consideration by credentialed intellectuals. He didn’t bear close attention. Wasn’t he a crank or cult figure? Once this view was infused among Western academics and opinion makers, it lingered for decades and made it unnecessary to look freshly and inquiringly at Gurdjieff; the conventional view was sufficient. For his part, Gurdjieff was likely content with isolation; the men and women who chose to work with him, who passed through the sieve of indifference and derision and found their way to him, were often brilliant in varied ways, always sincere and striving. In his lifetime that was all that was needed.

After early misrepresentations and gutter press reporting in the 1920s, when he did initially invite journalists’ attention to Movements performances and to the values and way of life at the Institute, he wanted nothing more to do with the media. As well, he had gained a reputation as a “hard” teacher, provocative and challenging—although privately with pupils, family, friends, and the impoverished Russian exiles in Paris who came daily to his kitchen for food, he was capable of life-changing kindness. He may have been content with marginalisation—there is a quiet atmosphere and fertile soil at the margin. But as I matured, and in the course of decades of participation in the teaching, I could not join Gurdjieff in that contentment. I experienced the gap as sad and sterile rather than as a moat that served everyone well.

In order to reunite Gurdjieff and his teaching to the Western mainstream, I knew that I should face his most severe critics, particularly those who assailed him in the decades after his death—and among those, particularly Louis Pauwels, whose book Monsieur Gurdjieff (1954 with revised editions to 1996, and English 1972) became the arbiter of opinion. This was an utterly interesting assignment. No previous author has looked as closely at the history, content, and consequences of assaults on Gurdjieff’s reputation. In a chapter of my book called “Derision”, Pauwels and others are heard, questioned, and I believe disarmed at last. Criticism of Pauwels’ kind was destructive. It left no good, and there was overwhelming good.

Gurdjieff’s teaching and at times his teaching style were great challenges. That was as it should be. He was both the Pythagoras and the Diogenes of our time: Pythagoras, the austere man of spirit, the musician and measurer of cosmos; Diogenes, the ironist and deliberate outsider, fearless and droll. Pythagoras in the esoteric redoubt of his school; Diogenes in the street. These ancient antecedent teachers were not easy; neither was Gurdjieff. But both were limitlessly inspiring to those who wished to be more, to know things not obvious but essential, and not least to know how and what to give others without vanity, in true service. This is the wide, for the most part unnoticed channel between Gurdjieff and Western culture. It is back at the headwaters and flows on from there.

There is so very much of value in Gurdjieff and his teaching that needs to be, yes, reconsidered. This was a very great human being. The teaching is a very great teaching. It is time, and past time, for thoughtful people to “take them on board”, to listen to the words and music, to experience—at the distance inevitably imposed by a book—the intensity of life and learning around Gurdjieff. The margin is no longer a generous enough terrain. Gurdjieff and his teaching belong closer to us as we do what we can to face and, insofar as possible, remedy the stunning difficulties of our time. Some will find a way to participate; others will, I trust, gain a new appreciation without choosing to participate. And those who still prefer to be critics of Gurdjieff and his teaching will have this book as a resource: start here.